Whanganui River restoration

Introduction

Whanganui River is included as a Ngā Awa river to ensure DOC can practically support the aspirations of iwi, hapū and whanau to progress its health and wellbeing.About Whanganui River and its catchment

The river begins on the slopes of Mounts Tongariro, Ngauruhoe and Ruapehu and flows for 290 km to the coast at Whanganui. Its major tributaries include the Manganui o te Ao, Retaruke, Ōhura, Ōngarue, Taringamotu, Whangamōmona, Tāngarākau, Whakapapa and Pungapunga rivers.

The catchment is large – 761,100 hectares – and includes Whanganui National Park. Half of the catchment is covered in native bush and one third is used for sheep and beef farming.

Download a map of the catchment showing sub-catchments (PDF, 3,084K)

Te Awa Tupua

The Whanganui River is recognised in law as Te Awa Tupua, a physical and spiritual entity that supports and sustains the life and natural resources within the catchment. Te Awa Tupua reflects the special status of the river which captures the unique relationship iwi and hapū have with the river and their responsibility for its health and wellbeing.

Te Awa Tupua is recognised through legislation as a legal person with the same rights, powers, duties and liabilities. It is an indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River and its tributaries from the mountains to the sea.

Working with Te Awa Tupua

Te Pā Auroa nā te Awa Tupua (a framework and set of indigenous values) guides our collective work with Te Awa Tupua. Organisations with an interest in the future of the Whanganui River including DOC, are represented on Te Kōpuka nā Te Awa Tupua strategy group. The group has developed a strategy document Te Kōpuka.

Restoring whitebait spawning habitat

In Whanganui, adult īnanga (whitebait) are known as atutahi. They make up most of the whitebait catch but have a conservation status of At Risk-Declining.

Atutahi lay their eggs (spawn) on riverbanks in autumn and sometimes in spring. The best sites are usually covered in long grass or native vegetation. Spawning sites are vulnerable to grazing animals, shading by large trees, steep slopes and hard structures that protect riverbanks.

Surveys of īnanga spawning sites

An initial survey of atutahi spawning habitat in 2019 showed a lack of suitable habitat and recommended more research be carried out.

We held a wānanga with hapū at Te Ao Hou marae in to discuss the habitat required for spawning and the methods used for surveying. The river’s potential spawning habitat was then surveyed in autumn 2021. Overall, the assessment showed that very little spawning habitat was available and highlighted the need to restore and protect spawning sites to increase the number of atutahi in the river.

- Read a blog and watch a video about this research

- View a summary of this 2022 research (PDF, 683K)

- Read the full report (PDF, 3,116K)

Habitat restoration – engineering report

A report completed in March 2024 outlines potential improvements for improving areas for atutahi spawning in the lower reaches of Whanganui River. It is based on previous research, discussions and suggestions made during field inspections, and the river’s character and dynamics. It includes options for reducing the slope of steep banks and replanting at selected sites.

Read the full report (PDF, 7,263).

We held a wānanga at Te Ao Hou Marae in February 2024 to discuss restoration options for atutahi spawning, particularly a stretch of riverbank beside the marae.

Watch an AWA FM video taken of the wānanga.

Read the Whitebait habitat a community effort: Media release 3 July 2024 about the planting event.

Planting projects

We are involved in planting projects to improve atutahi spawning habitat. This work includes hapū, the Pasifika Hub, Horizons Regional Council and Whanganui District Council. The planting sites are at Te Ao Hou Marae and Tutaeika, Awarua and Matarawa streams.

Other habitat restoration projects

Rata reserve restoration

Rata reserve is an area of public conservation land near the confluence of the Whakapapa and Whanganui River. We are working with hapū to restore this significant area. The work involves fencing, seed collection for planting, and animal and pest control.

Jobs for Nature projects

We worked with Ngā Tāngata Tiaki o Whanganui to develop a Jobs for Nature proposal. This enabled the Mouri Tūroa programme to be set up to fence and plant riparian areas in the catchment. The programme is led by Ngā Tāngata Tiaki o Whanganui and designed to create nature-based jobs for people who live in the area.

Another project, Ngahere Manaaki, was funded to plant mahoe and punga, and carry out predator control in the Whanganui catchment near Hiruharama/Jerusalem. Read more about this project.

Understanding the biodiversity of the river

Ecological health assessment

We worked with hapū to resurvey the ecological health of 10 freshwater sites in summer 2021/22, which were part of a larger survey in 1996/97.

While ecological health was found to be excellent at 4 sites, the other sites were in poorer health, especially those in areas of pasture. Overall, ecological health had declined since the previous survey.

Review of river biodiversity

A review of the existing information about the fisheries and biodiversity of the river was carried out in 2021. It included recommendations for restoration work and what further information should be gathered.

Exploring gravel movement and channel change

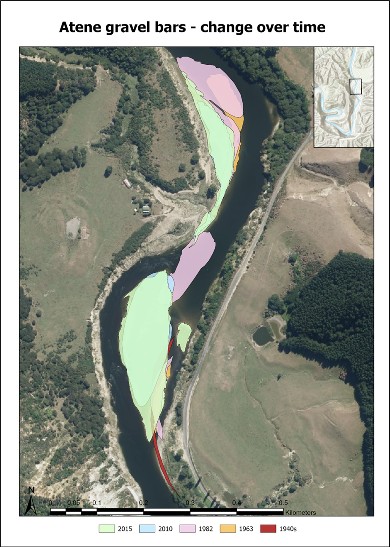

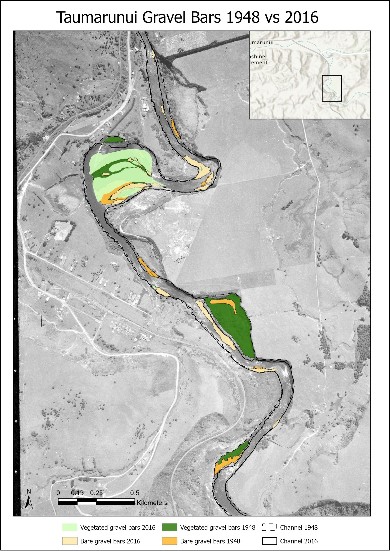

Changes in the geomorphology (size and shape) of rivers can affect the habitat beside the river and the biodiversity of the river itself. Two studies have investigated the geomorphology of the Whanganui River.

Ngāti Tuera and Ngāti Hinearo and DOC investigated the significance of gravel in Te Awa Tupua. The impact and loss of gravel, its effects on freshwater fisheries and the opportunities for enhancing or restoring habitat were studied.

A Massey University student mapped the changes in channel characteristics of two sections of the river from the 1940s to 2016 using historic aerial images. The work found that the mid reaches have been stable but the upper reaches near Tamarunui have been changed by straightening and narrowing.

A map of Atene gravel bars | See larger (PNG, 2,350K)

A map of Tamarunui gravel bars | See larger (JPG 701K)

Stream health assessment

The ecological health of a river can be monitored by counting the macroinvertebrates (bugs visible to the naked eye) at a particular site. The last comprehensive macroinvertebrate survey of the catchment was carried out in 1998.

We are working with hapū and whanau to assess the health of streams in the catchment using science and traditional knowledge. This includes re-surveying invertebrates at the same sites to see what has changed.

We are also supporting Te Kura o Te Wainui-ā-Rua to learn how to assess and monitor the health of a stream. On a stream health assessment day in 2021, students, parents and community helpers joined us to survey the stream and determine its mauri (life force).

Fish populations are usually surveyed with nets, electric fishing machines or by spotlighting at night. eDNA is a different approach, where all the DNA in a water sample is analysed to detect the presence of any fish species. This method will be used to survey fish in sub-catchments that are difficult to access.

Contact

If you have any questions or want to get involved, email us.

Email: info@doc.govt.nz