The history of kākāpō

Introduction

Discover the dramatic history of kākāpō, from despair to hope.Decline

Five of seven kiore/Pacific rats caught near a kākāpō's nest after a chick went missing, 1993

Image: DOC

Polynesian settlers

When the first Polynesian settlers arrived in New Zealand about 700 years ago, they found kākāpō to be easy prey. They ate its meat and used its feathers to make soft cloaks. With Polynesians came the Polynesian dog and rat, which also preyed on kākāpō.

By the time European settlers arrived in the early 1800s, kākāpō had become confined to the central North Island and forested parts of the South Island.

European settlers

The kākāpō’s demise was accelerated through European settlement. A great deal of habitat was lost through forest clearance, and introduced possums and deer depleted the remaining forests of food.

Devastating predators were also introduced: cats, stoats and two more species of rat. Kākāpō were in serious trouble.

Early conservation

Remains of one of Richard Henry's kākāpō translocation pens

Image: Andrew Digby | DOC

Richard Henry

In 1894, the government launched its first attempt to save kākāpō. Pioneer conservationist Richard Henry led an effort to relocate several hundred of the birds to predator-free Resolution Island in Fiordland. The island didn’t remain predator free though – stoats arrived within six years, eventually destroying the kākāpō population.

By the mid-1900s, the kākāpō was a lost species. Few people saw them, and no one actively cared for them. Only a few birds clung to life in the most isolated parts of New Zealand.

Finding males in Fiordland

From 1949 to 1973, the newly formed New Zealand Wildlife Service made more than 60 expeditions to find kākāpō, focusing mainly on Fiordland. Six were caught, but all were males and all but one died within a few months of captivity.

In 1974, a new initiative was launched, even though no birds were known to exist. By 1977, 18 more kākāpō had been found in Fiordland. However, there were still no females.

A breakthrough in Stewart Island/Rakiura

One of 18 kākāpō moved from Stuart Island/Rakiura in 1982

Image: Philip J Moors | Creative Commons

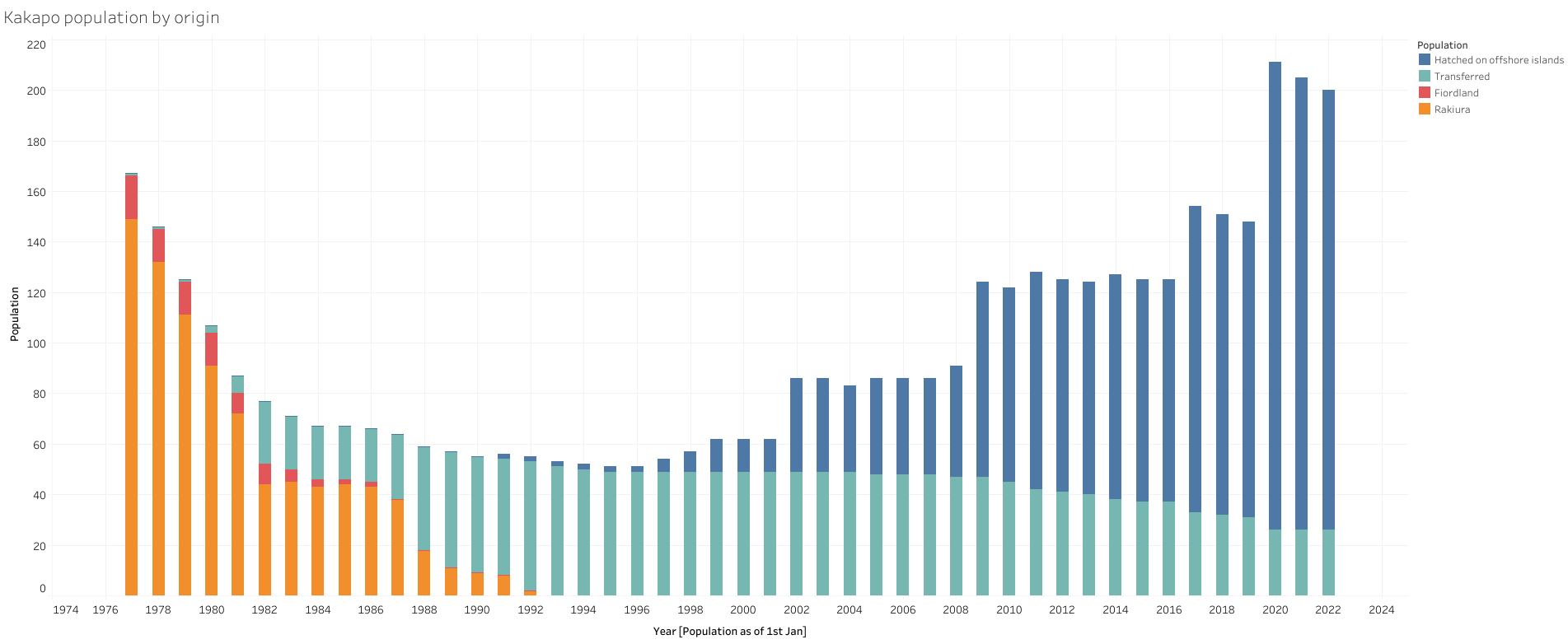

In 1977, a large population of males was heard booming in southern Rakiura – a large island free from stoats, ferrets and weasels. There were about 200 individuals, and in 1980 it was confirmed females were also present.

The Rakiura birds have been the foundation point for all subsequent work in managing the species. First by the New Zealand Wildlife Service, and since 1987 by its replacement, the Department of Conservation.

Island sanctuaries

Predation by feral cats had the Rakiura kākāpō in rapid decline. So during 1980–97, the surviving population was evacuated to three offshore island sanctuaries: Codfish Island/Whenua Hou, Maud Island and Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island.

Five Fiordland male kākāpō were also transferred to Maud Island during 1974–81.

The fall and rise of the kākāpō population over time

Rat predation

Even safe from cat and stoat attacks, breeding success was hard to achieve. Rats were found to be a major predator of newly hatched kākāpō chicks. Kākāpō could not produce sufficient chicks to offset adult mortality.

By 1995, although at least 12 chicks had been produced on the islands, only three had survived. The kākāpō population had slumped to 51 birds. The critical situation prompted an urgent review of kākāpō management in New Zealand.

A bold new plan

In 1996, the National Kākāpō Team was formed, along with a new ten-year Kākāpō Recovery Plan, increased funding and staffing and a specialist advisory group called the Kākāpō Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee.

Eradications

Cats were eradicated from Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island in 1980, followed by rats in 2004. Weka and possums were eradicated from Codfish Island/Whenua Hou by 1986, followed by rats in 1998. Stoats were eradicated from Anchor Island in 2001. The islands are now suitable long-term sanctuaries for kākāpō.

A kākāpō comeback

After the first five years of the plan, the population recovery was on target. By 2000, five new females had been produced, there had been 13 breeding attempts, and the total population had increased to 62 birds. There was a 68% increase in the total known population from 1995 to 2003, a total of 86 birds.

For the first time, there was cautious optimism for the future of kākāpō.

Today

Today, kākāpō management is guided by the Kākāpō Recovery Plan. The plan runs from 2006-2016, and outlines four key goals for the species.

- Maximise recruitment in the kākāpō population.

- Minimise the loss of genetic diversity in the kākāpō population.

- Secure, restore or maintain sufficient habitat to accommodate the expected increase in the kākāpō population.

- Maintain public awareness and stakeholder support for kākāpō conservation.

Our vision

Our vision is to restore the mauri (life force) of kākāpō by having at least 150 adult females.