Frequently asked questions

Introduction

Some frequently asked questions about the 2013 Code of Conduct for Minimising Acoustic Disturbance to Marine Mammals from Seismic Survey OperationsWhy have a Code?

Marine seismic surveying using energy from acoustic sources to determine sub-seabed geology can generate significant underwater sound. Depending on the energy levels produced underwater, marine mammals could potentially be impacted through direct effects (e.g. physical trauma) or indirect effects (e.g. masking communication, disruption to feeding).

Internationally, many jurisdictions have frameworks to manage such activities and mitigate potential impacts to acceptable levels. New Zealand established guidelines in 2006, and due to developments in international best practice, in 2010 it was considered timely to review and update the management regime.

Where does the Code apply?

To all New Zealand continental waters - this includes the Coastal Marine Area; the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); and the Extended Continental Shelf.

Under the EEZ and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects – Permitted Activities) Regulations 2013, seismic surveying is a permitted activity (i.e. no marine consent is needed), as long as the organisation undertaking the survey complies with the Code.

Contact the Environmental Protection Authority EEZ.Compliance@epa.govt.nz if you require further information about compliance with those regulations.

Who does the Code apply to?

Any person or organisation planning to undertake a marine seismic survey using an acoustic source; which could include the oil and gas exploration industry, scientific geophysical research, seabed minerals prospecting and cable-laying.

What about other activities that generate underwater noise?

Within the Coastal Marine Area activities such as pile-driving would be managed by the regional council under the Resource Management Act 1991.

The EEZ and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 also restricts the causing of vibrations (other than vibrations caused by the normal operation of a ship) in a manner that is likely to have an adverse effect on marine life in the waters of the exclusive economic zone.

In the EEZ (12-200 nm) regulations that address other effects on the environment are administered by the Environmental Protection Authority.

How does the Code relate to the Marine Mammal Sanctuaries?

There are six gazetted Marine Mammal Sanctuaries (MMS), five of which contain mandatory regulations for seismic surveying. In every respect the Code contains equal or more stringent provisions than the MMS regulations, except for relatively one minor requirement relating to the amount of time the acoustic source can be inactive before a soft-start is required.

The Code does not replace the MMS regulations, which remain mandatory and enforceable. However, stakeholders have agreed that where there are inconsistencies they will meet the more stringent provisions. In the future, DOC will implement consistent regulations throughout New Zealand waters under the Marine Mammals Protection Act (MMPA) 1978.

What are the most significant changes in the new regime?

Requirements for 4 independent observers, 24-hour Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) on Level 1 surveys and submission of a Marine Mammal Impact Assessments for all surveys are amongst the most important innovations.

Also, the strong focus on performance standards for marine mammal observers and PAM operators gives much greater confidence in the credibility of qualified observers. In general terms, the regime is now far more comprehensive and robust.

Who was consulted in the development of the Code?

The Code is a technical document, so it was considered appropriate to engage in targeted consultation with specialists and key stakeholders.

However, it was a broad and inclusive process, through which a wide range of representative organisations were offered a chance to participate, including environmental groups, industry, academics, government agencies and observers – both within New Zealand and internationally. Tangata whenua engagement was sought through DOC's established nationwide contacts.

Full public consultation will be undertaken when regulations are being considered under the Marine Mammals Protection Act 1978.

What is a Marine Mammal Impact Assessment ?

This is a similar process to an Environmental Impact Assessment, except the focus is on marine mammals only. The completion of the Marine Mammal Impact Assessment (MMIA) is the responsibility of the seismic survey proponent, and it has to identify all the potential impacts of their proposed activities along with the particular sensitivities in the region of operations, and identify all steps that can be taken to minimise or avoid negative effects.

The proponent also has to consult with interested stakeholders and specialists to determine the extent of known sensitivities.

The MMIA is submitted to DOC, which will review the information and provide any necessary advice. Additional mitigation measures considered to be necessary by DOC have to be implemented in the survey methodology.

What is an Area of Ecological Importance?

The Code provides a high degree of protection for marine mammals throughout New Zealand waters as a minimum requirement. However where particular sensitivities are known, extra precautionary measures may need to be considered.

DOC has analysed available databases for information on marine mammal distributions, and used specialist knowledge to identify Areas of Ecological Importance, which includes all the Marine Mammal Sanctuaries. As a result, publicly accessible GIS-based maps will be available on the website, which will be subject to ongoing reviews as new information comes to light.

Special interest groups and stakeholders with specialist knowledge about marine mammal sensitivities in their regions are able to engage with DOC in order to refine the maps if necessary. This map provides critical information to seismic survey proponents at the planning stage.

What does a seismic survey involve?

Level 1 marine seismic surveys are conducted using an array of airguns towed several hundred metres behind the vessel. This array uses the controlled release of high-pressure air at regular intervals to create intense low-frequency noises in the water directed at the ocean floor.

The sounds penetrate the seafloor, bounce off sub-surface structures, and are reflected back up to an array of listening devices towed several kilometres behind the boat. The reflected sounds can be analysed to learn about the geological structures below the ocean floor, typically to look for petroleum deposits.

How long will they go on?

Surveys can be from a single day to several months, depending on the type of survey and area covered.

Will rūnanga, fishing industry, other interest parties, and the community be consulted about the impacts on marine mammals and measures to protect the whales beforehand?

The Code requires anyone conducting an industrial seismic survey to submit a Marine Mammal Impact Assessment (MMIA). Among other things, in the MMIA the proponent must:

- Identify the actual and potential effects of the activities on the environment and existing interests.

- Identify the risk and consequence of any potential negative impacts.

- Identify persons, organisations or tangata whenua with specific interests or expertise relevant to the potential impacts on the environment.

- Describe any consultation undertaken with these persons.

- Include copies of any written submissions.

- Specify potential alternatives for undertaking the activity.

- Specify the measures to be taken to avoid, remedy or mitigate against adverse (or potentially adverse) effects.

Under the Code the expectation to conduct consultation with rūnanga and the community is placed on the organisation undertaking the survey. DOC facilitates this consultation by reviewing the organisation’s consultation list and adding any affected parties which are missing.

Will the community get to know the detail of how effects will be managed?

Once reviewed by DOC and assessed as sufficient to meet the requirements specified in the Code to the satisfaction of the Director-General, all MMIA documents will made available on the this website - see Marine Mammal Impact Assesments.

How will that affect the marine life?

Intense sounds have the potential to cause physical or behavioural responses from a variety of marine life, including marine mammals, squid, fish, and zooplankton. These responses could result in effects ranging from minor behavioural responses (reorienting away from the noise) to major injury resulting in death.

See below for further information on how DOC has specified protection zones to minimise the likelihood of negative effects on marine mammals.

How will the effects be monitored?

The Code requires independent, qualified Marine Mammal Observers and Passive Acoustic Monitors (2 of each) on board the vessel. These observers must have completed a DOC-approved course and demonstrated sufficient knowledge of seismic operations and their responsibilities under the Code. While onboard, the observers watch for the presence of marine mammals in the monitoring zones specified in the Code and ensure that mitigation actions are taken as specified in the MMIA.

Generally the mitigation action is that if marine mammals are detected in the zone, the sound source must be immediately shut down and can only be re-started after a period of observation to ensure that the animals have left the monitoring zone.

The observers must report any non-compliance to the EPA and DOC and the operator will be subject to enforcement action by the EPA. Standard reporting forms must be filled out and submitted to DOC after the survey, which will support future research into the potential effects of seismic surveying on marine mammals.

More distant monitoring for behavioural effects is not automatically required, but could be negotiated by rūnanga or other affected parties during the MMIA consultation process. DOC is generally supportive of any efforts to gain further understanding of the effects of seismic surveying on marine mammals.

What mitigation measures are put in place to ensure no adverse effects on marine mammals?

The primary mitigation measures are pre-start observation, “soft starts” and “mitigation zones”.

- Pre-start observation requires 30 minutes to 2 hours (depending on the context) of observation prior to activation of the sound source with no marine mammals seen in the mitigation zones.

- A soft start is the increase of the sound source volume from a low level up to full power over 20+ minutes.

Mitigation zones are the radius around the sound source that the observers must monitor for marine mammals. If any are sighted within the mitigation zone, the source must be shut down immediately. See below for further explanation of these zones.

How do we know they’ll work and not negatively impact on migratory mammals?

Any activity that introduces noise into the marine environment - industry, marine tourism, recreation, etc. - has the potential to affect marine mammals. The Code is designed to minimise the risk to marine mammals of injury or significant behavioural responses, but cannot guarantee that residual effects will not occur.

Behavioural responses might be observed well outside the monitoring zones designated in the Code, but expert assessment (see below for further explanation) is that these are unlikely to have a significant long-term consequence. With respect to migratory marine mammals, the Code clearly specifies that the best course of action is to avoid sensitive areas and times.

Are there any definitive science or case studies as to the impacts of seismic surveys on whales?

A variety of studies have been reported in scientific literature over the years, but there is no definitive answer as to the effect of seismic surveying on whales. Some animals/species have been reported as not reacting to the noise at all, others have been observed moving away when the vessel was many kilometres away. Humpback whales have been observed moving rapidly away from the sound source, as well as moving rapidly toward it.

The bottom line is that reactions can be very different depending on the species, location, type of noise, and other factors. No deaths or strandings of marine mammals have been directly linked to seismic surveying, but naval sonar (a very different type of loud sound) has been implicated in both and is often confused with seismic in popular media. Nonetheless, a genuine concern exists about the potential effects of seismic surveying on marine mammals, and DOC has developed the Code to minimise this risk.

What are the mitigation/monitoring zones?

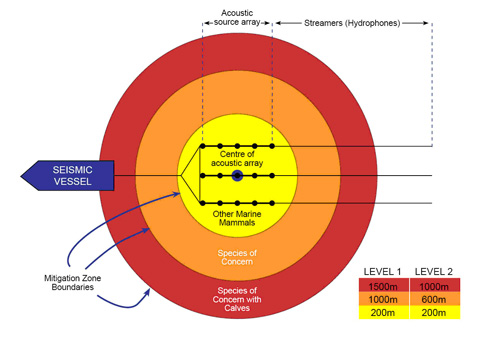

A mitigation zone is a circular area of a specified distance around the centre of the sound source. This area is continually monitored by qualified marine mammal observers, who have the authority to delay or shut down the survey due to the presence of a marine mammal. The Code splits surveys into three levels, depending on the size of the sound source used:

- Level 1: the highest power surveys, generally used by the oil and gas industry for exploration

- Level 2: less powerful surveys, often used for scientific research by NIWA and GNS

- Level 3: includes all other small-scale seismic surveys – with noise levels less than commercial shipping – and is not covered by the provisions of the Code.

Under the Code there are three mitigation zones for Level 1 and Level 2 surveys, determined according to the sensitivity of the marine mammals to which they apply and the potential effect of the sound levels likely to be encountered at that distance from the source. The diagram below outlines the key distances.

See below for how these zones compare to other international standards for monitoring and mitigation. Species of Concern are listed in Schedule 2 of the 2013 Code of Conduct (PDF, 1,060K), and include all species of whales found in New Zealand, most species of dolphins, and New Zealand sea lions.

What is the basis for the monitoring zones in the seismic Code?

The monitoring zones are designed to minimise the risk to marine mammals of injury or significant behavioural response likely to result in injury. The Code describes two critical levels of sound in water:

- The level of sound likely to result in injury = 186 decibels

- The level of sound likely to result in a significant behavioural response = 171 decibels.

These sound levels are based on published scientific recommendations from a panel of international experts on the effects of sound on marine mammals, which you can access - see Aquatic mammals (PDF, 3,810K). The levels above are the sound levels which the panel designated for the most sensitive marine mammal groups, and thus are the most conservative recommendation available. As a simple basis for comparison, sperm whale clicks have been measured at up to 232 decibels, and many marine mammal species can produce sounds at around 190 decibels.

The transmission of sound in water is very complex, and depends on temperature, depth, underwater geology, and other factors. Over the years, researchers have built a sophisticated understanding of these factors, and built mathematical models which allow them to input specific details of the sound source, temperature, depth, etc. and accurately predict what the likely sound level is at a variety of distances from the source.

Using the characteristics a typical oil and gas airgun, researchers at Curtin University estimated sound levels to be 165 decibels at 1 to 1.5 km from the source. This indicates that the monitoring zones under the Code for Species of Concern (all whales and most dolphins in New Zealand) are sufficiently large to ensure that sound levels will be below the behavioural response/injury levels described above.

Can the monitoring zones be made larger?

Yes. If a survey is conducted in an Area of Ecological Importance (PDF, 1,280K), the survey company is required to include sound modelling in their MMIA. This modelling is generally contracted to university researchers, who use the specific details of the airguns and the temperature, depth, and bottom geography of the survey area to create an estimate of the likely sound levels at the monitoring zone boundaries.

If the estimated sound levels exceed the levels described in above, the survey company is required to reduce the sound level or expand the monitoring zones. Larger areas might also be negotiated during the consultation process to address specific community concerns.

How do these monitoring zones compare to international standards?

In the UK, Greenland, Gulf of Mexico (USA), Canada, Brazil, and Australia, 500 m is used as the zone for shutting down the airguns due to the presence of marine mammals. A number of other countries follow the UK standards and use 500 m, while Ireland uses 1000 m. Therefore, the New Zealand zones can be considered significantly more conservative and likely to provide a higher level of protection than found elsewhere in the world.

Why does DOC rely upon modelling of sound?

As noted above, modelling of sound is very complex and dependent upon a lot of factors which may not match the actual conditions when the survey takes place. However, it is the best way to estimate in advance what is likely to happen, and allows us to adjust the monitoring zones if needed prior to the survey beginning.

Does anyone measure the actual levels of sound during the survey?

Yes, the survey company is required to use their equipment to record the actual levels of sound at the monitoring zone boundaries, and compare those back to the modelled estimates. These comparisons will then be provided back to DOC and will be used to inform any future changes to the Code.

Why isn’t the company made to measure sound levels in advance?

This has not been considered for a number of reasons. In order to be accurate, it would require the exact vessel and airguns to be in place and to fire at full power to collect the data, which would introduce more noise and additional risk to marine mammals. In order to be included in the MMIA, this testing would have to be conducted at least a month in advance, and many of the factors which affect transmission of sound can change significantly in a month.

What about a night, or when visibility is bad – how do you see marine mammals then?

The Code requires the use of Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) technology to be used during surveys, which allows the detection of marine mammal noises underwater. PAM is a combination of sophisticated listening devices and computer software to filter and identify marine mammal noises. This is why the Code requires 2 PAM operators during any large survey, as they are monitoring for marine mammal noises 24 hours a day when the airguns are active.

Does anyone else require Passive Acoustic Monitoring to be used?

Internationally, most countries consider it “best practice”, but do not require it to be used. Greenland and Canada require it at night or during reduced visibility, but New Zealand is the only country which currently requires the use of PAM at all times as an automatic requirement.

Is this the best we can do?

It is DOC’s belief that as a whole, this system provides a higher level of protection than any other in the world. One of the strengths of the Code is that it is built to grow and change as we learn more about marine mammals and seismic surveying. We fully intend to review the Code on an ongoing basis, to ensure it continues to provide a high level of protection.

Isn’t stopping seismic surveying the lowest risk option? Can’t DOC just do that?

DOC has no power to decide whether individual seismic surveys occur. Area-based restriction of seismic surveying is possible within Marine Mammal Sanctuaries, and elsewhere the Code is the best way to ensure that the activity poses a low risk to marine mammals when undertaken.