Research shows change to Hector’s dolphin distribution in Akaroa

Archived content: This media release was accurate on the date of publication.

Introduction

New research has found a change in Hector’s dolphins' summer distribution in Akaroa Harbour, with fewer sightings in the inner harbour coinciding with an increase in cruise ship visits.Date: 21 October 2022

Akaroa Harbour in Te Pātaka o Rākaihautū (Banks Peninsula) is valuable habitat for the nationally vulnerable and endemic Hector’s dolphin. The beauty of the harbour and the resident Hector’s dolphins are the basis of a locally important and nationally significant marine tourism industry.

Researcher Will Carome, of the University of Otago Department of Marine Science, analysed 20 years of the University’s dolphin survey data to determine which parts of the harbour dolphins were being seen in and compared it to trends in cruise ship and dolphin tourism. Almost 370 surveys, recording 2,335 dolphin encounters from 8,732 kilometres of boating, were analysed.

The research found a clear shift in the summer distribution of Hector’s dolphins in Akaroa Harbour during the last 20 years, with dolphins becoming less likely to be seen in the inner harbour.

The shift in distribution predominately occurred at a time when cruise ship numbers in Akaroa increased, following damage to Lyttelton Port from the February 2011 Christchurch earthquake.

The research does not prove what caused the distribution change, but suggests disturbance from cruise ships is the most likely explanation.

In summer 2009/10, Akaroa hosted seven ships and 6,222 passengers. By summer 2011/12, there were 77 ships visiting the harbour bringing in 127,341 passengers. Large numbers continued to visit until Covid-19 restrictions began in 2020.

Cruise ships are returning this summer, but far fewer (17) are scheduled to visit Akaroa as the new Lyttelton cruise ship berth has opened. The boats visiting are generally smaller luxury boats.

Will Carome says the research aimed to determine whether the distribution of dolphins may have been influenced by human pressures during the last 20 years.

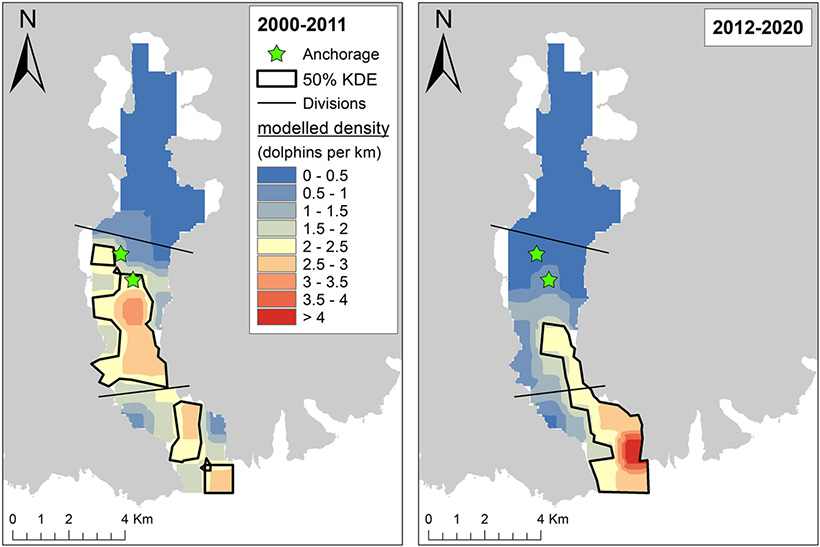

“To do this, we used a technique called ‘kernel density estimation’. Essentially, we input data from sightings in mapping software to create a heatmap showing how likely one would be to find dolphins in a given area.

“This method also shows us core use areas for the dolphins, known as hotspots. These are outlined in black in the heatmaps. To examine whether distribution has changed at Akaroa, we divided the study period into 2000–2011 and 2012–2020, before and after the increase in annual cruise ships.”

Kernel density estimation of summer Hector’s dolphin sightings at Akaroa Harbour for 2000-11 and 2012-20. Black outlines show dolphin hotspots, or core use areas. Green stars show the primary anchorages for cruise ships at Akaroa.

Image: Will Carome | ©

Will Carome says it’s important to note the strong correlation between increased cruise ship visitation and changes in Hector’s dolphins' presence/distribution in Akaroa Harbour does not necessarily mean cruise ships were the cause of the changes. Other potential drivers, such as changes in sea temperature or prey distribution, could have played a role in the shift.

“However, there are several impacts associated with cruise ships that are likely to influence dolphin habitat preference, including increased noise, increased vessel traffic, and damage to the seafloor that may impact species Hector’s dolphins eat.”

Will Carome says the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a remarkable opportunity for both management and research, giving marine life short-term relief from some human impacts.

“With the future of cruise ship tourism changing, our findings suggest the future development of this industry should follow a precautionary approach.”

DOC Mahaanui Operations Manager Andy Thompson says DOC is working alongside Ōnuku Rūnanga, the regional council Environment Canterbury, tour operators, researchers, and the community with the aim of protecting the dolphins and reducing any potential impact of cruise ships, dolphin tour vessels and general vessel traffic.

“The Hector’s dolphins are an important part of Akaroa and the people who live here feel a strong connection to them. We want to work with local people to find solutions that benefit everyone and are also focused on the wellbeing of the dolphins.”

In 2010, research highlighted Akaroa’s Hector’s dolphin population has been exposed to some of the highest tourism pressure in New Zealand and the activity has been shown to significantly change their behaviour.

In 2016, DOC placed a 10-year moratorium on the issuing of any new marine mammal tourism permits in Akaroa Harbour and commissioned the University of Otago to conduct additional research to fill knowledge gaps and inform further permit/vessel traffic management decisions. This new research was paid for by a research levy collected from the operators.

Background information

Hector’s dolphins are one of the world’s smallest dolphins at about 1.5 m long. Classified as nationally vulnerable, there are about 15,700 in New Zealand’s waters, primarily around the South Island.

Set net and trawl fishing and the parasitic disease toxoplasmosis are the biggest threats to the dolphins, with threats also from seismic surveying, seabed mining, tourism, vessel traffic, oil spill risk, coastal development, pollution, sedimentation and climate change.

Located 75km southeast of Ōtautahi Christchurch, Akaroa Harbour is one of only a handful of spots around the world where visitors are more likely to see dolphins than not. A twice-daily replenishment of nutrients from strong tides breathes life into this flooded crater, left behind from a volcanic explosion some nine million years ago.

The University of Otago began annual surveys of the Hector’s dolphins (Cephalorhynhcus hectori, tutumairekurai, pahu, tūpoupou, popoto) in Akaroa in 1984. The invaluable dataset is among the longest running studies on dolphins in the world.

Read more about Hector’s dolphins.

Contact

For media enquiries contact:

Email: media@doc.govt.nz