They start out as tiny leaf-shaped larvae, live most of their lives in freshwater and when fully grown, make a long journey through the Pacific Ocean to breed.

Eel species in Aotearoa

Three species of eel are found in Aotearoa:

- Longfin eel (Anguilla dieffenbachii). Conservation status: At Risk- Declining. Found only in Aotearoa.

- Shortfin eel (Anguilla australis). Conservation status: Not Threatened. Found in Aotearoa, Australia and some Pacific Islands.

- Australian longfin eel, speckled longfin eel (Anguilla reinhardtii). A visitor from Australia.

About eels

Eels are long-lived fish that spend some of their lives in freshwater and some of it in the ocean. In freshwater, eels like to live in cool, shady water out of direct sunlight – often tucked away under logs, boulders or near riverbanks. They are generally more active at night, hunting for food.

Longfin eels can be found throughout New Zealand, and are by far the largest native fish. They live mainly in rivers and inland lakes but can be found in almost all types of water, usually well away from the coast. Shortfin eels tend to live closer to the sea.

Eels have a very slippery skin with tiny, deeply embedded scales that can only be seen under a microscope.

Wild eels can be hard to spot. Some parks and zoos attract eels that you can see up close and sometimes feed.

There are many things we don’t know about eels. Studies of their fascinating lifecycle and behaviour continue to reveal more information about them.

Tuna – a taonga species for Māori

Tuna is the most common Māori name for freshwater eels. Tuna are taonga, a treasured species to Māori.

Information about tuna and their importance to Māori in te reo Māori and English.

Lifecycle of eels

Larvae are translucent and leaf-shaped

Eels begin life in the Pacific Ocean. Their eggs hatch out into tiny, flat, leaf-shaped, translucent larvae called leptocephali. The larvae are carried on ocean currents to reach rivers and streams around New Zealand.

Glass eels enter river mouths in spring

By the time they arrive, the larvae have grown longer and rounder but are still translucent. These are now juveniles called glass eels.

Glass eels gather offshore before they enter river mouths in large groups. After a few days in freshwater, they develop a brown pigment in their skin. This colouring provides good camouflage for their lives in streams and rivers. Once they are coloured, the juvenile eels are called elvers.

Elvers grow and move inland

Elvers are excellent climbers and make their way inland via most rivers. Elvers can climb steep waterfalls up to 20 m high, and even some dams. They can even leave the water and wriggle upwards over damp ground to get past obstacles.

It takes several years for elvers to reach inland areas where they continue to grow and mature.

Becoming adults and a final migration

Eventually eels settle into their adult habitat and grow into large fish. Longfin eels are often more than 1 m in length but can grow up to 2 m. Adults can reach 20 kg. Shortfin eels are generally smaller, growing up to 1 m long and weighing up to 3.5 kg.

This takes many decades – some female longfin eels are estimated to be more than 90 years old. Unlike other fish, eels grow slowly, only 15–25 mm per year. The biggest eels are usually old females that have been slow to reach sexual maturity and have not migrated to the sea.

Just before they migrate downstream to the ocean, adult eels change to a silver colour and make the long journey back to the Pacific Ocean.

Eels are thought to spawn in deep ocean trenches. The exact location of their spawning grounds is still unknown, but some scientists think they are near Tonga. Females lay millions of eggs that are fertilised by males. Eels die after spawning and do not return to Aotearoa.

The average lifespan for longfin eels is 35–52 years, but they can live for up to 100 years and sometimes longer. Shortfin eels have an average lifespan of 18–23 years but can live for up to 60 years.

What eels eat

In rivers, small eels feed on insect larvae, worms and water snails that live in the gravel. Larger eels prey on fish, kōura (freshwater crayfish) and small birds like ducklings.

Eels have a well-developed sense of smell that they use for hunting prey. They have tube-shaped nostrils that stick out at the front of their heads, above the upper lip.

Eels also have very large mouths with rows of small, sharp teeth. The top teeth form an arrow shape on the roof of their mouths.

How to tell longfin and shortfin eels apart

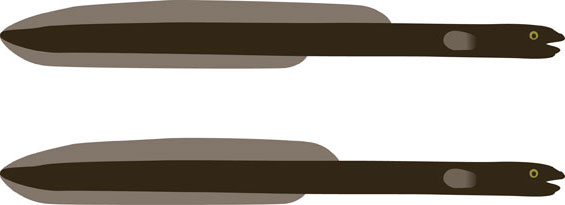

As their name suggests, longfin eels have a longer top (dorsal) fin than their lower (anal) fin. The top and bottom fins are closer in length for shortfin eels.

Diagram of eels with longfin at the top and shortfin below.

Longfin and shortfin eels also have obvious differences in the way their skin wrinkles. The skin on longfin eels forms big, loose wrinkles when it bends, while the wrinkles on a shortfin’s skin are much smaller.

Longfin eels are usually a darker colour than shortfins. Longfins can also live further inland, favouring clear mountain streams. Shortfins generally stay nearer the coast and don’t mind muddy water.

An eel is probably a longfin if it is:

- very dark in colour

- more than a metre long

- living in a clear, cold, spring-fed stream or a high-country river or lake.

Australian longfin eels look like New Zealand longfins but have black blotches along the top of their bodies.

Monitoring eel populations

Many iwi, organisations and groups monitor eels in their local area. This can be specifically for eels or as part of general environmental monitoring.

We support and lead several eel monitoring programmes:

- Ashley River glass eel monitoring programme. This is the longest glass eel study in Aotearoa and has been running for more than 30 years. It was begun by NIWA and is now led through our Ngā Ika e Heke programme.

- Lake Rotoroa eel monitoring with Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō. Read more about this project in a Conservation Blog.

Fisheries New Zealand has supported an elver monitoring programme at selected locations since 1995. Read the 2023 report.

Recreational and commercial fishing

Shortfin and longfin eels can be caught by recreational, customary and commercial fishers across New Zealand, apart from in protected areas like national parks and DOC-managed reserves.

The recreational bag limit is 6 eels per day. Commercial harvests are managed through the Quota Management System. Fisheries New Zealand assesses the commercial and customary eel fishery each year. Read the 2024 report.

See more information about fishing for eels, including rules: Freshwater eel fisheries

Threats to eel populations

Populations of longfin eels across Aotearoa are declining. Shortfin eels have stable populations.

Changes to the environment, like pollution, sedimentation, climate change, diseases, overfishing and loss of habitat are all potential threats to native eels. Dams and weirs that stop eels moving up and downstream, also put significant pressure to their populations. Shortfin eels tend to be less vulnerable to these changes than longfins.

Hydroelectric dams and weirs

Although eels are able to climb steep waterfalls, barriers like dams, weirs and culverts can stop them moving up and downstream. Both elvers and adult eels are affected by these barriers, which prevent them from getting to suitable habitat and completing their lifecycles.

Eels can also be injured or killed when they try and move past hydroelectric turbines on their journey to the ocean. Eel passes have been built across some dams to help them get over the dams. In some places, adults and elvers are collected and moved across the dams by hand.

Drains, irrigation and polluted water

Drainage, irrigation schemes and river diversions threaten eel populations. These changes to rivers and streams can damage or take away the habitat that eels depend on.

Polluted water also affects the survival of eels – longfin eels are particularly sensitive to this threat. Chemical spills and discharges of sewage and industrial wastewater are the most common cause of mass eel deaths.

Algal blooms, nutrient run-off from land and fast-growing plants can also reduce the amount of oxygen dissolved in water. Eels are sensitive to this change, which is made worse by high water temperatures.

How you can help eels

Eels are wild animals. Respect their space and habitat:

- Create cool, shady habitat for eels beside streams by fencing out stock and planting natives.

- Join a community catchment group that’s working to restore a stream or river in your area.

- Don’t throw rubbish or waste into waterways.

- If you see a large number of dead or dying eels call MPI on 0800 80 99 66.

More information

Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment report: On a pathway to extinction? An investigation into the status and management of the longfin eel